Stalking the Prey

Looking at the above code, the first obvious optimization that developers suggest seems to be taking the conditional out of the loop, resulting in several case-specific loops. On small vectors, this nets about a 30% speedup. For further speedups, the suggestions are typically to go for loop unrolling, asm, and other heavy-handed solutions that come with a significant development time and code complexity increase.

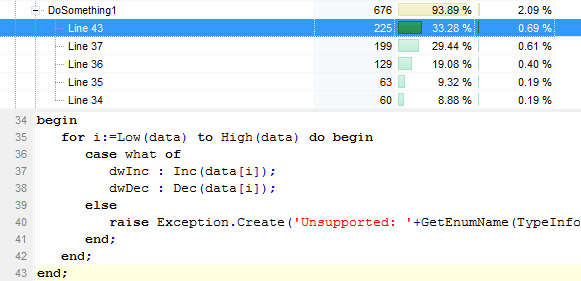

Of course, readers of this website will know better than to jump straight into the code and apply optimization recipes: they would run the code through a profiler first. And since we’re dealing with a single procedure, an instrumenting profiler would be of little help, so they would run Sampling Profiler instead, and would get to see something like this:

In this run, only the dwInc case was stressed (line 37), and obviously the procedure spends less than 30% of its time doing what it was asked of, and most of its time (33%) on the “end“, ie. cleaning up, plus 8% setting up in “begin“. That’s 40%+ doing nothing but stack and setup/cleanup work!

The conditional in the loop that could have looked like the most worrying bit is eating a bit less than 20% of the time.

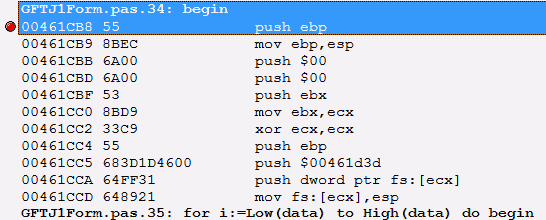

What is the source of all that begin/end work? Place a breakpoint on begin, run and hit Ctrl+Alt+C when your breakpoint is reached, go have a look at the CPU view, and you’ll see this:

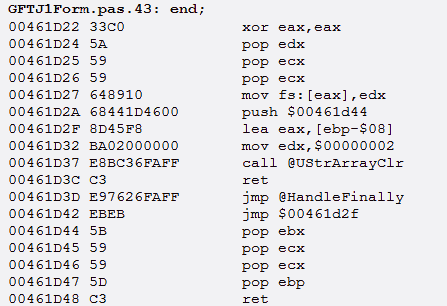

This is a fairly significant stack setup for such a small procedure, and those instructions with “fs:” at the bottom are the setting up of an (implicit) exception frame. An exception frame for what? if you haven’t guessed already, navigate your CPU view near the “end” line.

No wonder “end” was a bottleneck! The call to UStrArrayClr indicates that the exception frame is here to cleanup several strings… these strings are those of the raise Exception, one is the string returned by GetEnumName, the other is the result of the concatenation passed to Exception.Create.

Isolate and Kill

How to get rid of that exception frame? One typical way is to use “Exception.CreateFmt”, and pass only constant strings to it, but that is not possible here with the call to GetEnumName, which returns a string. The other way is to isolate the exception to its own (nested) procedure:

procedure RaiseUnsupported(what : TDoWhat);

begin

raise Exception.Create('Unsupported: '+GetEnumName(TypeInfo(TDoWhat), Integer(what)));

end;

and call RaiseUnsupported in the “case else“. Doing so will move the exception frame to the new procedure, where it’s irrelevant in terms of performance.

This simple change nets us a 33% speedup, ie. we reclaimed most of the lost time in begin/end! We also gained a bit from the UStrArrayClr, which did essentially nothing since those strings it was used to clear weren’t defined (as long as we did not hit the exception).

Note that if you use a nested procedure for RaiseUnsupported, you can be tempted not to pass it the “what” parameter, but use directly the “what” from its parent procedure. However by doing so, you’ll have the compiler use a special stack setup (so that the nested procedure can access the parent procedure’s variables). This setup will be faster than the exception frame it replaces, but with it, begin/end would still be taking about 18% of the CPU time spent in the procedure.

> the compiler won’t “know” about the exception in the called procedure

That’s something that I really miss in Delphi. You can’t give the compiler a hint that a procedure never returns. C++0x has something for this but Delphi doesn’t. Maybe somebody should file a feature request in QC.

Good article! This reminds me I need to try your SamplingProfiler on some of my code, hopefully I will help me remove some bottlenecks.

> the compiler won’t “know” about the exception in the called procedure

The approach I’d have taken would have been to have a utility function that returns the Exception to be raised.

ie: line 105 to read

raise CreateUnsupportedException(what)

and defined as

function CreateUnsupportedException(what : TDoWhat): Exception;

begin

Result := Exception.Create(‘Unsupported: ‘+GetEnumName(TypeInfo(TDoWhat), Integer(what)));

end;

Wouldn’t that still remove the Sting cleanup code into the function but also allow the compiler to “see” the raise.

Good work mate! Thank you for this very educational example.

i think this is one of the most helpful technical articles, on any subject, that i’ve ever seen. It starts with a real example, and it deals with the real questions that result. And what’s good is that you actually focus on the weird stuff, explain why it is, and how to fix it – or why it should not be fixed.

By dealing with the tough questions, in the same way that they would occur to another developer, you make the task of optimizing seem obvious and natural.

Actually saying that a CreateFmt would be the first fix, but then explaining why it won’t help in this case, is perfect.

Yes, great educational article, thank you Eric.

But interestingly I tested this same procedure under Delphi 7 as an exercise to become familiar with SamplingProfiler, and in my tests the exception frame overheads were insignificant.

The time spent on the “end” statement in DoSomething1 varies between 0 and 11%.

I tested with array sizes from 40,000,000 to 200,000,000 integers, with the following typical number of samples for each array size:

Array size: 40M 80M 200M

DoSomething1 105 212 544

DoSomething4 104 211 539

So it seems to me that with Delphi 7 it’s not worth the disadvantages of moving the exception to a procedure.

Or am I missing something? (The “stack setup” line did not appear in any of my profiling, nor did the “case of” line for DoSomething4).